Daughters of Uranium (2019–2020)

Discursive strata entangle transformations. Chemical transformations (e.g., Trinitite, the residual green and red glass formed when the heat from the blast met the gypsum sand), entangle with emotional and ecological transformations. These transformations include the built structures and operations of the test, its accompanying organizations, bureaucracies, and militarization, and the site’s communities of scientists, historians, and families. Discursive strata also engage intellectual and scientific pursuits and their resulting discussions, studies, and publications within, for example, a sub-discipline like post-atomic studies. The framed archive, itself another intercalary fold within these overlaying experiences, explores how Mary Kavanagh’s photographic and research-creation is a civic performance, wherein the visitors, photographer, and audience are participants in the discourses specific to this site. In interviewing visitors, she perpetuates the discourse of the site, and as she has said, develops a “feminist imperative to constellate the narrative” beyond military culture and affect, economics, rationalizations, and ethics.

Kavanagh’s Daughters of Uranium (2019–2020) is a narrative told through an archive. As a storyteller and an archivist, Mary Kavanagh blurs the distinction between what is past and what is present. She overlays official archives of the past, such as the Los Alamos National Laboratory archive, with those of her own. Her personal, material archive can be measured in generations with a photograph of her grandmother that she exhibits. The archive she installs and exhibits is not always material. A few chemistry-glass vessels each contain one of the artist’s exhalations.

[21] Peter C. van Wyck, “Reading the Remains,” in Daughters of Uranium by Mary Kavanagh (Lethbridge: Southern Alberta Art Gallery, 2020).

[22] Guyatri Chakravorty Spivak, Death of a Discipline (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 72.

[23] Ele Carpenter, Nuclear Culture Source Book (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016), 99.

Kavanagh’s most recent exhibition at the Founders Gallery in the Canadian Military Museums explores how our shared atomic legacy imprints itself onto the body over generations through a combination of approaches to making and collecting. As Peter C. van Wyck writes, Daughters is a “Wunderkammer for the nuclear age, an atomic archive, documentation of a legacy demanding something larger than grief. These works have the effect of shifting public perception of these sites from an exclusively territorial domain to the domain of the body.”[21] The atomic bomb set in motion a new domain of armed engagement from a distance, expanding fields of violence that could overwrite the globe.[22] From this view, Kavanagh’s exhibitions that feature her archives, body, and constellations of memories and diligent attention to those narratives facilitate the development of “social and creative structures for cultural inheritance.”[23]

Kavanagh’s work now has renewed cultural purchase in tracing the contours of atomic legacies and nuclear memory imprinted on collective, intergenerational memory and inscribed within the body. Even before walking into the gallery, I was met with a vast field of neon green on the wall facing the door. As I walked through the corridor to get to the gallery space, the uranium-green provided an increasingly sharp contrast to the dusty, muted, aged colors of the preceding World Wars exhibits that exhibit paraphernalia from Canada’s involvement with wars, After entering the white and naturally lit space, to the right is a letter, dated August 7, 1945 from modern painter Georgia O’Keefe to Photo-Secessionist-era photographer Alfred Stiglitz, which describes a loud blast she heard two weeks ago in the early morning. She felt her house shake, and she wonders how he is feeling, “now that we have a new and most powerful bomb.” The letter is laid out in a glass-cased plinth to the left of a mounted and framed New York Times Newspaper from August 6, 1945, a day after O’Keefe dates her letter. The headline reads, “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan; Missile is Equal to 20,000 Tons of TNT; Truman Warns Foe of a ‘Rain of Ruin’.” The text covers the entire first page of the newspaper symmetrically.

To the left of this wall was another square, glass-enclosed plinth with twenty to thirty pieces of Trinitite, a new metal the sky exhaled, after being sucked up from the ground and chemically transforming on its way up through the blast’s turbulent vacuum; to the left, two photographs of Trinitite from the 1945 and 1947 appear with the photograph’s metadata briefly describing and dating the photograph at the bottom half.

Around the corner from the Trinitite and its photographs are thirty-two archival photographs, with metadata, that depict daily operations and loading preparations. The pile of lead bricks would have been used to line walls to protect workers from radiation, due to its chemical composition’s molecular capacity to refract ultraviolet light. Again, mirroring this is a pile of roughly sixty lead bricks. In another photograph, three lead bricks, arranged askew, stand vertically on a board. In another, an unceremonious pile of about thirty unpolished lead bricks sits behind a descriptive sign, “lead bricks / T machinery / about 100 yds / north of / crater.” “T” machinery refers to machinery used in the Trinity test. In another photograph, about twenty bricks are haphazardly piled alongside other unknown material. The data at the bottom of the photograph reads, “Remarks: Instrument shelter about 60N looking S.W. / Lead bricks have been nested. Note original brick placed in photograph for comparison.” All but one of the bricks are unpolished, grainy, and round around the edges, whereas one polished, straight-edged brick has been posed as some exemplar for comparison.

[24] Kavanagh received a master’s degree in art history from The University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario.

In the exhibition, a sample of six lead bricks sit on the floor. Here, Kavanagh acknowledges the male-dominated discourses of late-modernism when she stacks the six lead brick samples. Exhibited like this, it might closely resemble works by Carl Andre or Donald Judd, male artists who enjoy a privileged place in the history of American art, a history with which Kavanagh is familiar.[24] However, her presentation of the samples is an allusion to another piece in the exhibition. The stacked bricks directly reference one of the archival photographs she includes in the grid. In this way, she uses the photograph as source material, perhaps in the spirit of Joseph Kosuth, to recreate the work and re-present the figure of stacked lead bricks in a new archive-cum-exhibition space. This rearticulation is one that extends the photographic archive into a physical space – and the photographs of the lead bricks in the field and their polished representatives on the gallery’s floor. The photograph on the wall, the exhibition of it on the floor of the gallery, and the subtle reference to late modernism allows the work to exist in at least two discursive spaces: the often unseen and sparsely rummaged-through space of the library or archive and the exhibition space in first, a university art gallery and then in a Military Museum in Alberta, Canada.

[25] Christina Cuthbertson, “The Book Unbound: Nuclear Entanglement in the Work of Mary Kavanagh,” in Daughters of Uranium by Mary Kavanagh (Lethbridge: Southern Alberta Art Gallery, 2020), 101.

Borrowing Truman’s warning broadcast through the newspaper, Kavanagh’s series Rain of Ruin: Concept Studies (2011–2019), is a collection of animal and shape studies in watercolors. The series began “as an exercise for Kavanagh to capture an insight, an image, a bit of information, as she labored through texts and archives, films and photographs about nuclear armament, environmental catastrophe, the militarization of medicine, animal testing – and ultimately the series became a record of a thought process, an underwriting for Daughters of Uranium.”[25] As Kavanagh moves through the archive as part of her research practice, she conducts the concept studies to reference throughout the exhibition of her other materials. In one of these watercolor studies, she has sketched an outline of a pig; in another, a pig anti-radiation suit. It was built for an adolescent pig, an animal that shares many features with human skin and hair follicles. Then she references her concept of the pig suit while exhibiting an actual anti-radiation suit for pigs. The Atomic Tourist: Trinity dual-channel video projects onto the wall on a screen in the northwest corner of the gallery space. Behind the viewing bench was an enclosed viewing room, lit by blacklight. Inside, a set of legs, made out of the same material as the irradiated hands, lay in the middle, emitting a bright, seemingly unnatural light. Around the corner was an anti-radiation suit, formerly used in testing related to radiation effects on the skin, mirroring the physical product in Pig Suit.

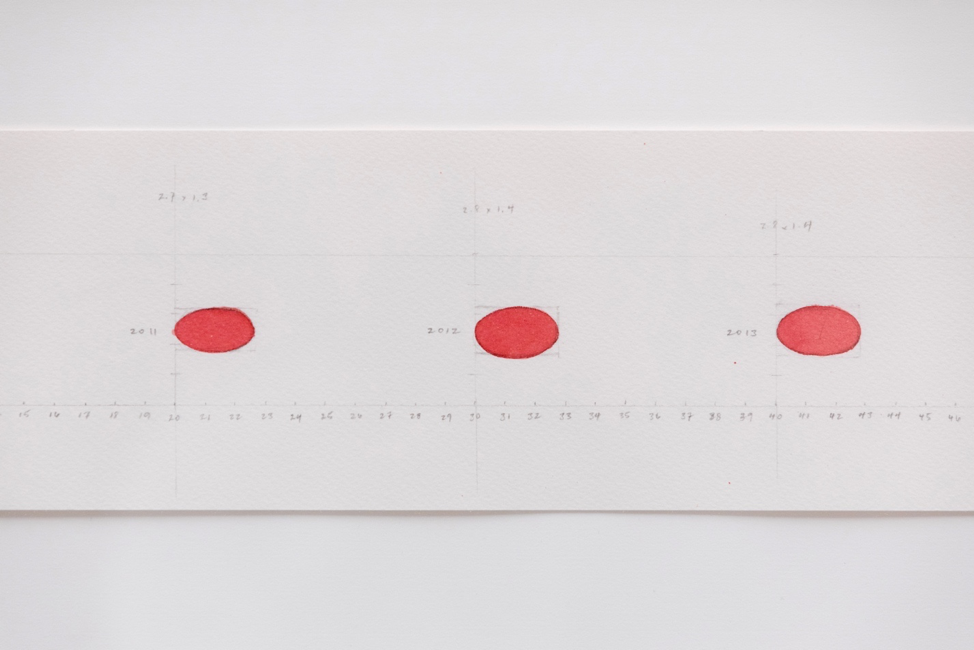

The exhibition ends at the left of the gallery’s entrance, with three artifacts. One is a coral-red watercolor of three ovals, measured by inches, by the year, in pencil. The second is a photograph of a young girl, who has been brought outside in a wheeled chair. The third artifact, visible from the entrance, is a painting of a figure emerging from an underground chamber amidst a miasma of yellowish-brown vapor.

[25] Christina Cuthbertson, “The Book Unbound: Nuclear Entanglement in the Work of Mary Kavanagh,” in Daughters of Uranium by Mary Kavanagh (Lethbridge: Southern Alberta Art Gallery, 2020), 101.

Borrowing Truman’s warning broadcast through the newspaper, Kavanagh’s series Rain of Ruin: Concept Studies (2011–2019), is a collection of animal and shape studies in watercolors. The series began “as an exercise for Kavanagh to capture an insight, an image, a bit of information, as she labored through texts and archives, films and photographs about nuclear armament, environmental catastrophe, the militarization of medicine, animal testing – and ultimately the series became a record of a thought process, an underwriting for Daughters of Uranium.”[25] As Kavanagh moves through the archive as part of her research practice, she conducts the concept studies to reference throughout the exhibition of her other materials. In one of these watercolor studies, she has sketched an outline of a pig; in another, a pig anti-radiation suit. It was built for an adolescent pig, an animal that shares many features with human skin and hair follicles. Then she references her concept of the pig suit while exhibiting an actual anti-radiation suit for pigs. The Atomic Tourist: Trinity dual-channel video projects onto the wall on a screen in the northwest corner of the gallery space. Behind the viewing bench was an enclosed viewing room, lit by blacklight. Inside, a set of legs, made out of the same material as the irradiated hands, lay in the middle, emitting a bright, seemingly unnatural light. Around the corner was an anti-radiation suit, formerly used in testing related to radiation effects on the skin, mirroring the physical product in Pig Suit.

The exhibition ends at the left of the gallery’s entrance, with three artifacts. One is a coral-red watercolor of three ovals, measured by inches, by the year, in pencil. The second is a photograph of a young girl, who has been brought outside in a wheeled chair. The third artifact, visible from the entrance, is a painting of a figure emerging from an underground chamber amidst a miasma of yellowish-brown vapor.

[28] Mary Kavanagh, in conversation with the author at the exhibition, December 6, 2019.

[29] Lindsey V. Sharman, “Flu War Breath Cloud,” in Daughters of Uranium by Mary Kavanagh (Lethbridge: Southern Alberta Art Gallery, 2020).

The first, the watercolor, seems to be a two-dimensional chart of a function of time and size (units are in square inch). The first, labeled “2011,” reads “2.7 x 1.3.” The next two, labeled “2012” and “2013,” read “2.8 x 1.4.” Here, Kavanagh has measured the growth of a tumor, still extant, in her right lung. Tumour Timeline is, like Mack and Brixner’s space-time relationships, a series of data points that trace the size and shape of the tumor over time. What she then demonstrates is a graphical interface that corroborates an externalized,[16] three-dimensional anomaly in the body, in a sample size of three along an x-y axis (time-size). When paired with her grandmother’s photograph and the painting, it would perhaps be easy to pair a cause and effect with relation to the tumor’s timeline, but this is perhaps more of a suggestion, much like O’Keefe’s letter to Stiglitz and the front page of the New York Times.

Drawing from her personal archive is a photograph of the artist’s grandmother as a young girl, recovering from an operation in the same lung, the right one – a surgery necessary after her contraction of the Spanish Flu. She recovers from influenza and the operation with the help of the only known but unreliable remedy, fresh air.[27] After recovery, the girl in the photograph would become a chemist in the 1920s and 1930s.[28] The photograph was taken in 1918, the same year Varley, below, finished the painting, commissioned by the Canadian government.

On the wall’s other side was a painting by Frederick H. Varley, one of The Seven – Canada’s founding landscape painters – completed in the same year. These measurements are placed on the wall, obliquely, from the other two artifacts, the photograph of Kavanagh’s grandmother and Varley’s painting. In the painting by Varley, Gas Chamber at Seaford, a figure with protective covering from head to toe emerges from an underground test chamber used to develop the chemical weapon, mustard or chlorine gas, evidenced by the green-yellow-brown fog swelling from the chamber alongside the soldiers emerging of the tunnel.

These three artifacts are linked together through a motif – the necessary process of breathing, a requisite to sustaining life. Inhaling and exhaling, an involuntary yet critical function of the human body, bends and bows through Kavanagh’s exhibition, especially in Daughters of Uranium’s concluding section. They act as three visual interpretations of deadly environmental conditions: a graph, a photograph, and a painting. When seen in the context of the whole of the exhibition and the Canadian history museum complex, these totems of air quality and their suggested causes and effects are metonyms of toxic ecologies and their entanglements with military history. Paired with the Trinitite on the other end of the gallery, the viewers see the chemical transformation of oxygen into carbon dioxide within cycles of respiration. On the Trinitite in the gallery, Lindsey V. Sharman observes, “the atomic bomb inhaled the desert sand and exhaled Trinitite.”[29]

[26] For more on the externalization of biometric data, the retrieval of this data for future use, and the archiving, quantifying, and categorizing of biometric data, see: Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter 1986): 3–64.

[27] The Spanish Flu created an epidemic that raged in 1918 during the First World War. Ninety-nine years later, this exhibition recalls pressing and prescient visualizations of the current global, public health concerns.

Mary Kavanagh’s “discursive strata,” conceives of stories as an archive for intimate personalization of tourist narratives, ones that cleave from Kenneth Bainbridge’s initial tourist-like, survey photography in the 1940s. Atomic Tourist: Trinity and Daughters of Uranium, Kavanagh’s latest exhibition and photographic practices demonstrate that photography can indeed offer an effective anti-conflict politics, one that may activate conscientious viewership that realizes social transformation. Photography does indeed emerge as a necessary civil right, responsibility, and duty.